Update for Sept. 3: As of 5 a.m. EDT, Hurricane Dorian has weakened to a Category 3 storm.

As Hurricane Dorian churned across the Bahamas Monday (Sept. 2), the storm's awed astronauts in orbit with its raw power and set NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida on high alert for potential damage.

As of 11 p.m. EDT (0200 GMT), Dorian was stalled just north of Grand Bahama Island as the Category 4 storm battered the island with maximum sustained winds of nearly 130 mph (215 km/h), according to a National Hurricane Center update. Earlier Monday, the storm was hard to miss to astronauts looking down on Earth from the International Space Station.

"You can feel the power of the storm when you stare into its eye from above," NASA astronaut Nick Hague wrote on Twitter while sharing a striking photo of the storm. "Stay safe everyone!"

Video: Here's the Latest Video of Hurricane Dorian from Space

Watch: See Hurricane Dorian in Action in these Gifs from Space

NASA astronaut Nick Hague of the Expedition 60 crew snapped this photo of the eye of Hurricane Dorian, a Category 4 storm, from the International Space Station on Sept. 2, 2019 as the storm stalled over the northern Bahamas.

Hague's crewmate Christina Koch, also of NASA, snapped several more views of Dorian as the space station flew 260 miles (418 kilometers) overheard. Her four-photo series reveals the storm's eye up close, as well as views of the entire hurricane as it crossed the northwestern Bahamas.

"Hurricane Dorian as seen from Space Station earlier today," Koch wrote on Twitter. "Hoping everyone in its path stays safe."

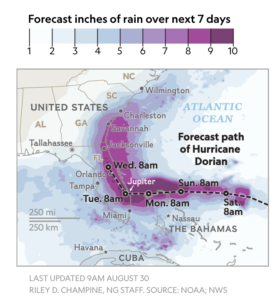

At least five deaths have been attributed to Hurricane Dorian so far as the storm slammed the Bahamas with high winds and flood-inducing storm surges, according to the New York Times. Current models forecast Dorian will slowly turn northeast, approaching close to Florida's eastern shore and moving northward along Georgia and the Carolinas.

"On this track, the core of extremely dangerous Hurricane Dorian will continue to pound Grand Bahama Island into Tuesday morning," NHC officials wrote in their update. "The hurricane will then move dangerously close to the Florida east coast late Tuesday through Wednesday evening, very near the Georgia and South Carolina coasts Wednesday night and Thursday, and near or over the North Carolina coast late Thursday and Friday."

Related: How NASA and NOAA Track Hurricane Dorian from Space

With Hurricane Dorian forecast to bring hurricane conditions to the Kennedy Space Center in just a few hours, 120 members of the “Ride Out Team” reported to the Launch Control Center to monitor and mitigate possible damage to spaceflight hardware #HurricaneDorian @NASA

Dorian's Florida approach has set NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral there on high alert.

On Monday, the space center called in a skeleton crew of 120 workers, called a "Ride Out Team," to monitor the storm's effects on the spaceport and protect spaceflight hardware from damage. The team will oversee the space center during Hurricane Dorian from the historic Launch Control Center near the Pad 39 launch complex.

Photos from the space center showed KSC workers with camping backpacks, luggage, coolers and even an inflatable mattress, blankets and a space shuttle plush toy.

Meet Madi: She’s riding out #HurricaneDorian in our Launch Control Center, where our firing rooms are. Once its safe to go out, this industrial hygienist and her team immediately do a post storm hazard analysis at KSC. And if you can’t tell, she loves @NASA!

A contingent from the U.S. Air Force's 45th Space Wing, based at the nearby Patrick Air Force Base and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, is also at the Launch Control Center to help out. One Kennedy Space Center video shows military personnel making their way inside the Launch Control Center with their own supplies.

With #HurricaneDorian bearing down on the Space Coast, our friends from the @45thSpaceWing arrived to the @NASA Launch Control Center to shelter during the storm. Even the General is here!

"With Hurricane Dorian bearing down on the Space Coast, our friends from the 45th Space Wing arrived to the NASA Launch Control Center to shelter during the storm. Even the General is here!" KSC officials wrote on Twitter, referring to Brig. Gen. Douglas Schiess, who has commanded the 45th Space Wing for the last year.

The newspaper Florida Today is offering a live video stream of NASA's Kennedy Space Center courtesy of the paper's Space Team. The video stream, which is available directly from the Space Team's Facebook page, shows a view from the Space Team's building at the Kennedy Space Center, with views of SpaceX's facility at Launch Pad 39A and the United Launch Alliance's pad at Launch Complex 41 of the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

You can also see it embedded below, courtesy of Florida today.

If you live along Hurricane Dorian's path, visit the NHC and your local National Weather Service office for the latest forecasts. You can find the latest updates on Dorian from the NHC here.

- NASA Sees Hurricane Dorian from Space Station (Video)

- NASA's Kennedy Space Center Prepares for Hurricane Dorian

- Photos: Most Powerful Storms of the Solar System

Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Have a news tip, correction or comment? Let us know at community@space.com.